Walking On Water

In the summer of 2013, I was 44 years old. I feel like myself only in summer, the kind of person who is miserable for the long Cleveland months when the temperature is below, say, 64 degrees. Obviously, I live in an inhospitable climate. But during the summer months, I am alive. I carry spare shoes everywhere with me in my car to walk outside, I practice yoga in parks on tree stumps or bridges, and I don’t begrudge the ugly humidity that makes everyone look shiny and slimy, with dirty hair. I love and embrace it all. It’s easier for me, no doubt, because I am currently taking a break from employment to finally go to college full-time, so I don’t need to put on layers of spackle and hairspray, dress in a suit or Spanx, or worry about armpit stains on my blouse. I gladly parade my sweat as I walk with my ear-buds tightly placed, eating as many meals outside as possible and refusing to come indoors. These summer days, as hot and oppressive to some as the whoosh of air which accosts your face when you open an oven on Thanksgiving, are what I spend the rest of the year waiting for.

This past summer, however, my Polish/Irish/Lebanese fair-in-winter, olive-in-summer skin had barely seen the outdoors. It was the summer of Hap—that’s my dad’s name—again. Two years prior, it was also a summer of Hap, when my dad took a final rapid slide down into a well of a dementia marked by hallucinations, violence, and delusions. Since then, my mom and sisters, along with our husbands and children, had visited him daily in his residential nursing home—a nursing home made necessary by his physical strength and that of the aggressive delusions which plagued him; hallucinations of people harming us, his family, which left him no choice but to try to take down the aggressors. Our dad, our defender.

Over time, Hap grew weaker, physically and mentally, and then, the summer of Hap 2013 became about his final days. He had been hospitalized for a while with digestive issues which seem unresolvable at that point in his illness, and then he had been sent to hospice-care to transition through to death. My family members and I had seen nothing but the inside of his medical bedrooms for the better part of two months. In the end, we were grateful that his final time occurred in the summer, because his grandkids were home from school and around to visit him, and to spend time within the cocoon of the very last days we would all be together as a complete family, the finals weeks, days, hours, minutes with our beloved mentor and patriarch, our team captain.

The time was rich; irreverent, fruitful, angry, dark, food-filled, and emotional. We ate fistfuls of Honey-baked ham and packaged cookies to pass the time. We talked, recalling old memories…we sang (John Denver, poorly), we mocked each other. We chastised my dad, who was mostly unconscious and certainly unaware by this point, for keeping us cooped up all summer. We made funeral arrangements. One day in July, I slipped out into the sunshine to a waiting bench near a statue of Jesus, and I wrote out my dad’s eulogy in longhand, a speech I had been giving in my head for years, knowing always that it was incumbent upon me to try to do this remarkable man justice in words. A nun saw me from the window of my dad’s room and assumed I was sunbathing. I did not correct her. There was something perversely funny to me about tanning in the back of a Catholic institution meant for the dying.

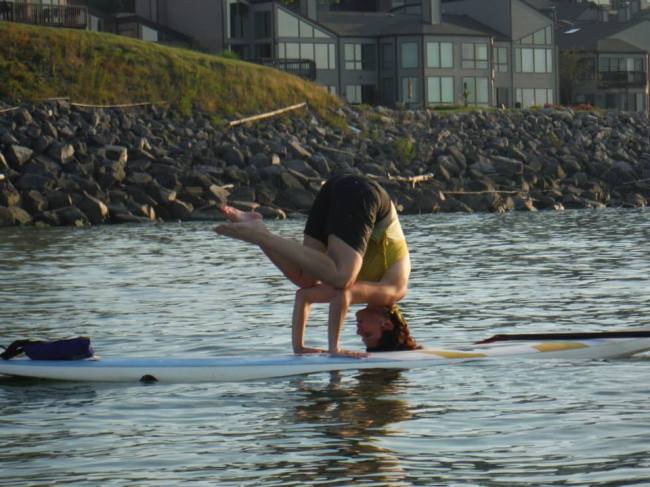

After more than a week in hospice, I looked at my calendar one day at my dad’s bedside, and realized I had signed up for a stand-up paddleboard yoga experience on Lake Erie for the next day. I’m sure it had seemed like a grand idea at the time, a group decision with a couple of yoga friends. The daughter my dad had known would never have attempted this—I was not an athlete by any means, spending much of my life a little overweight and a lot under-exercised. I was not a strong swimmer, if you could call me a swimmer at all, and I don’t know if you could. I may or may not be able to keep my head above water and make some progress in a time of trouble on water, but I’m not certain the resulting action could accurately be labeled “swimming.” Yoga was the only exercise I did, and even that was the result of my recent search for peace during my dad’s illness, not any physical prowess. I also have a healthy fear of large bodies of water, and no confidence in my ability to perform this scheduled outing. It was decidedly out of my comfort zone.

I texted my yoga-friend Jenny, because the excursion had already been paid for, and I hoped that she could find someone to take my place and enjoy the experience. But as the day went on, I felt a nagging pull at my consciousness to consider leaving my dying father’s bedside for a few hours to do something completely out of the ordinary. I was scared, not only of being able to navigate the actual physical activity, but that after all of these days and nights spent in this room, my dad might slip away during the one time I was absent. To be truthful, I also feared the impression it would leave with others: my family, the nurses, the general “people” who would undoubtedly ask, “what kind of daughter would leave her dying father’s bedside to go play watersports on a summer evening?”

I think it was that final bit, though, that actually convinced me. My dad, a man of many unique and wonderful characteristics, was most known for walking his own path, no matter what anyone thought. He sold investments to wealthy clients wearing a Cleveland Indians tee-shirt (he was about to be buried in one, too). He drove goofy vehicles which had personality (most recently a cobalt-blue turbo-charged Subaru) no matter how luxurious a car he could actually afford, and he took his wife (our mother) on all of his business trips because he wanted her to see the world with him. If he knew that I was bailing out on something I’d committed to simply because I was afraid of how I would look to other people, he would shake his head at me. It began to occur to me that this activity could actually be a tribute to my dad, that he would get me through it and inspire me to appreciate the beauty and accomplishment and camaraderie of what I was about to undertake.

I had a talk first with Paula, the wonderful hospice nurse who had been taking care of my dad every weekday of his hospice stay. She was a friend by then, it being such an intense time for sharing family stories and feelings with intimate strangers. She also knew my dad, his physical condition, very well. It had started to deteriorate more rapidly, and we knew the end was nearer than it had been. I asked, “Paula, what should I do? If I have a thing to do tonight, do you think it’s okay for me to leave to do it? Or is he close?”

Paula (who by the way, my dad would have absolutely loved and would have probably nicknamed something like “Scrappy” because she was small but fierce), looked towards my dad’s bed, looked back at me, and repeated both actions. Then she said, “You know him. What would he tell you to do?” Well played, Paula. And right on. So, with the confidence born from the knowledge that nothing else can possibly even matter when you’re about to lose someone forever, I walked out of my dad’s room that evening, not knowing if I would see him again alive. Of course, as I grasped his hand and kissed him goodbye, I said (as I always did), “See ya tomorrow!” But I felt like something had changed. Something bigger was happening, and it almost felt as if my dad had already left that body.

Incidentally, one of the most valuable things about hospice for us was the way that it gave us our dad back, restored to his old self in a way. The dementia had been so grueling, and his perceptions and statements so out of character, that once he was debilitated enough that he could no longer speak, we were left with his beautiful blue eyes (for the first day or two, until he became semi-conscious at best) and the feeling that he had been delivered from dementia, and instead lay dying here as his former self, in his right mind. The hospice caregivers changed his bedding every day before we even arrived, shaved him, brushed his teeth, washed his hair, made him look like he was in his own bed at home, no longer hooked up to IV’s or tubes. So when I leaned over him that day, he smelled of shaving cream, toothpaste, and soap, just the way I remembered him. I carried that smell with me as I drove away, recalling how it would come down the stairs ahead of him on Sundays, when he was the last one ready as the rest of us waited to leave for church. A man with a wife and three daughters is last in line for a shower.

The day was one of the hottest that July, maybe in the nineties. Despite that, I drove to the lake with my windows and sunroof open, drinking in the moist heat and the dangerous feeling that I was somewhere I was not supposed to be. I felt fragile, and grateful that the friends I was about to meet for this excursion were not close friends yet. They were women around my age, with similar interests and problems, compassionate and supportive, but I knew they would not ask me questions, hug me too tightly or lingeringly, or ask if I was okay. They knew, probably better than I, what I was there for that day and the restorative power it might have over me. They had each already buried a parent. Their support was silent, but loud. The remaining participants were strangers. It was a welcome feeling to just be an anonymous body as we all schlepped the cumbersome paddleboards off of a trailer and toward the Great-Lake Erie. Only my two yoga friends knew that I was in a liminal space, “the one whose father is actively dying.” But we couldn’t concentrate on that: we had to worry about getting up, and then staying up, on the boards bobbing under us on the water inside the break wall of the lake.

Once we were all assembled and following the leader, I noticed bystanders watching from shore. Looking through their eyes, I realized that we looked fierce, like models on a women’s magazine, unaware of our ages and instead feeling like lithe, strong teenagers. We had on an assortment of swimsuits, board shorts, yoga clothes. No cell phones, no watches, just sweaty hair up in ponytails because all of us still wear it long (I heard somewhere that if a woman can remember Gerald Ford being President, she is too old to wear a ponytail). We attentively listened to Deanna, our instructor, who seemed to embody light: blonde hair, bronzed skin, with a strong and casual manner, competent. We were in good hands. We had already developed some confidence in our strength through yoga, these friends and I, but we were all shy about our abilities on this giant, often angry lake. There was little conversation, only concentration, bodies held at attention, and deliberate motion.

As we traveled up the shoreline, past indescribably unique and lovely homes and a bit away from the safety of the shore, Deanna led us through yoga poses. Yoga inherently employs “pratyahara,” the act of suspending the senses, of coming inside…so while there was a handful of us sprawled out some yards from each other, going through the same motions, we each practiced in isolation. I could feel my friends Jenny and Beth near me, all of us supporting each other with our presence, with our intention, and our breath, sending waves of friendship out from our hearts even as we were fighting hard to maintain various balances on a floating board. We generated immediate and copious sweat, which ran down not just our faces but our entire bodies, pooling in our bellies when we lay on our backs, making our hands slippery when we stood inverted in downward dog. We were ruddy, our ribcages heaving with exertion, slow, steady exertion. It was like being squeezed out, a sponge from a pail of water. Loose hairs frizzed around our faces or stuck to our temples. Any remnants of old mascara had long since smeared away.

I opened my eyes and squinted around me, the glare of the fiery evening sun slapping the dark glassy water, the sky so bright my friends were rendered just silhouettes to me. My eyes burned from the salty brine of sweat, wind, and emotion. It occurred to me that my dad was just such a silhouette now, too. I suddenly felt positively impervious to any attack, ten feet tall and bulletproof. I was aware of my upper arms and shoulders rippling in smooth strength as my paddle dipped into the water, pushing my hips forward, potent. I was as strong as I had ever been, as beautiful as I would ever be, and as capable as any other person on the planet. Without warning, I sensed my dad’s presence so strongly around me that I said aloud to my friends, “I know now that there is absolutely no place else on earth that I should be at this moment then here on this lake with you.”

I wondered if this sudden peace and feeling of connection with my dad meant that he was slipping away, even as I was gliding along in this moment of bliss. I contemplated what I would feel like if my dad took his last breath while I was on this lake, while my mom and sisters sat close and held his hands and spoke soft words to him. I knew in that moment that it would be perfectly correct if that’s the way it happened. My inner voice reminded me that I was the one who lived next door to my parents, I was the one who worked with them for fifteen years. Maybe it would be a wonderful gift to my sisters for them to finally have as much of a portion of my dad as I had always been so spoiled to have. If he passed away in my absence, I would not regret my decision to choose this spiritual experience of my dad on this lake.

At the end of our practice, as we drifted, lying on our backs on the paddleboards with the cinnamon-hot July sun setting behind us, I closed my eyes and felt buoyant in mind and spirit. This body of mine, this body of water, and this body of friends and family was stable and certain. This mighty lake may as well have been the very palm of my dad’s hand, and the deep, wide well of his heart. I relaxed. I thought of my dad’s broad, brown hands and how they had held me up on countless summer vacations, held me by my ribs in oceans and hotel pools, tossing and playing with his kids like toys. We were never afraid. He always caught us, held us aloft. He always would. The palm of my dad’s hand, the palm of our Father’s hand. More gargantuan and mighty than this lake, but tender, both.

Swirling, floating, feeling more accomplished than the accomplishment merited, I sensed rather than saw the sun melt low and hot into the horizon, and wondered without fear or anxiety if my dad’s light had just dipped below the surface of this life. I celebrated Savasana, the yoga pose of relaxation, drifting on a trembling sunset, feeling and tasting hot, wet salt on my face, sweat mixing with healing tears, as welcome as they were valuable, flowing unchecked. I never felt closer to my dad than at that moment; I’d never loved or appreciated him more.