(2012?)

The best, worst hour of every day is the hour (or two, but that just doesn’t sound as catchy, now does it?) that I visit my dad, especially now. Initially, it was many hours at a time, unless it was a hospital behavior ward which limited the visits to one or two hours. But back in those days, whether it was one hour or several, things were more “worst” than “best” for sure. There was nothing to be grateful for at that time, other than the fact that my dad was safe. It was too soon to smile about memories and be grateful for all that he had been. We were still in the thick of it, losing him while he fought us and was angry with us for letting him be sick. I don’t know when he let go, I don’t know when he knew how much and what was drug-induced and what wasn’t.

My mom still has a telephone message on her voicemail from him from three months in, around September, when he was maybe in one of the hospitals or else early on at Manor Care North Olmsted. She played it for me yesterday, and in it he sounded so sweet. He asked how she was feeling, noting that he hadn’t been feeling great, and that he didn’t have his phone (he would ask the nurse’s station to call my mom for him in the early days) but that she should try to get ahold of him whenever she could. It’s a mystery to me when he might have left this, because she was simply there almost all of the time. I had a message saved on my voicemail too, from October. I received it while Jeff and Mom and I were in Florida, packing up their now sold retirement home – another emotional story for a different chapter. In the message to me, he was agitated because he somehow had the idea (he would wake up with these ideas, probably from dreams but then didn’t make the distinction between dream and reality – either that or he just flat out hallucinated it) that my mom was angry with him, accusing him of seeing another woman. He wanted to impress upon me that of course that was absolutely not true, there was no other woman, and would I please convince her of that? When I switched from a Blackberry to my IPhone, I was told the message could not be saved. I was initially very upset, but I know that it already wasn’t my dad, and while I would love to have his voice with me always, it really IS in my head. I’m sure I won’t always be able to hear it, but that’s the nature of things.

It is so hard to describe his early illness and nursing home “incarceration” because he was still very much Hap, and yes fought us on things. But at the same time, his fight wasn’t convincing because while he knew who all of us were and that he was mad at us, he also thought concurrently that he was on a cruise ship or at the office. So you see, we really did have to do what we were doing, and never know who/what you’d get when you went to visit.

I’m going to go back to the past later, but for a different perspective, let’s talk about today since it is fresh in my mind. It was a completely uneventful visit, but still pertinent to the subject of “the best hour, the worst hour” of my day. Parking your car at the nursing home is never a fun thing – what’s next, you know, is to walk into a place that is familiar, too familiar, but unfamiliar as well. You don’t want it to be familiar, it’s for other people. The anxiety grips you as you walk towards the door, because you know what kind of smells are going to hit you when you enter, and that there will probably be at least one person hanging out in a wheelchair, looking like nothing you’ve ever wanted to allow into your life. Maybe they are just literally hanging there, belted in. Their head is probably lolling to one side, perhaps they are drooling. Perhaps they can say hello to you, but many times they cannot. Now that you’re “a regular,” the sight of such a person no longer disturbs you and you smile and greet them by name. That’s part of the paradox of the best/worst. It never gets less gross, disgusting, inhumane, or horrifying. Yet you embrace all of those things, and the people to whom they are happening, with compassion. You don’t notice that Bob’s hair is always greasy and never combed and that he spits when he talks. You don’t care that the food is all over the faces and down the fronts when you are in the dining room with the others. You don’t balk at seeing the top of the diaper out of someone’s pants, or people without their teeth. You stop noticing the damaged toenails of the diabetics or the nose-picking of the guy with the really long fingernails that no one ever seems to cut. They are beautiful and you come to love them for what you know they must have been once. You see your own mortality, frailty, and probable future, and you have compassion.

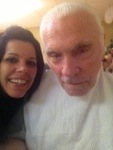

But before that, let’s be honest, it sucks. Today, I went at lunch time, and my dad was already seated at “his spot” in the dining room, by the window. He had been shaved, which is always a plus – because he looks like my daddy again, clean-shaven, beautiful skin. To see him look disheveled, although it is common now, is nothing like the dad I knew (unless we’re talking early morning before the shower – then that white hair was wild!). Now, though, showers are about every three days in the nursing home. That part is done by the aides, so we get to ignore or forget what exactly that process looks like. Does my dad just sit there on the shower chair? Does he participate, or let them do all of the work? Is he ever “with it” enough to be embarrassed any more? He made a comment to my mom once at the Manor, pointing out a giant FEMALE aide, and telling my mom “she gives such a good shower!” If that’s not proof my dad was ‘gone’, I don’t know what was. The man was ridiculously modest, especially around women. I can’t say that enough times or with enough emphasis. So, today, my dad was clean shaven, hair combed back, and that made him look good. He was also sitting up straight, which helps the illusion of health also; some days, he is leaning over to the left, drooling and with one arm draped over the wheelchair. He matched today, thanks to whomever took care of him. His sweatpants and sweatshirt matched or complemented each other, which is always a toss up.

You may think that we are uninvolved, that we could demand he be put in a particular outfit every day, that he doesn’t like this, doesn’t like that – but we found out fairly early on that most of those type of demands aren’t for the patient, if we’re being honest. They are for the family, so it doesn’t hurt so bad. Dad has no idea if he matches, and no one there does, either. Earlier at the Manor, if his shirt was inside out or something didn’t match well, we might mention it or try to fix it for him. All this did was to confuse my dad. It was to make US feel better, not him. Because he felt just fine with it backwards or whatever. That’s part of the learning process for us – the prettier nursing home (which couldn’t keep him locked in), the demands on what he wears and eats (which he no longer has a clue about) and things like phones and television remotes (which he loses, or adds to his hallucinations, or throws), and even the photos and calendars and mementos we have placed all around him in his room, are for US. He lives in a very particular world, and those things do not matter. In fact, they interfere.

Today, his appearance made me say “hey, good lookin’!” And I leaned over him to give him a hug. He hugged back, which he doesn’t often do, and he smiled. He seemed strong today, awake and aware. Not aware he has dementia and is in a nursing home, but more aware that it is daytime, I am sitting with him, and that he should pick up his fork and eat lunch. Other days he looks vacant, hazy, or has his eyes closed even as he mumbles as if we are speaking . Still other days he “answers” someone calling to him a few feet away, a hallucination. Some days, he needs help eating, having no idea or no desire to engage with the food, or because in his mind, he is in a different reality. He will treat his napkin like a form and his finger like a pen and begin working, despite the plate of food in his way. But today, he was pretty good. He burped, and then laughed. A return to being a baby, is how I look at it. He looked at me sheepishly, and I told him he was just cracking himself up, that all men were seventh grade boys at heart. He liked that, and he laughed and looked at me.

Nowadays, those are the days that make me cry. When my dad smiles, not a polite smile for someone else but a smile because he is chuckling at something, there is nothing in the world that is more beautiful for me to see. He was always such a good looking man, and smiling was such a part of him. When he smiles at me, with those blue eyes and beautiful face, I miss my dad. Those few times are glimpses into the happy, Happy man that he was. And happy for Happy was a deliberate choice. He was filled with natural optimism and glee, but he just refused to be anything but happy, no matter what the situation. And I love him for that, and I embrace that lesson from him, but oh, how fast the tears come, though I’m smiling through them, when he smiles at me. Then I hug him, and kiss him.

The meal is always a variable, too. Today, he was drinking okay by himself from a normal cup. I keep meaning to take a milkshake to ascertain whether or not he can still drink out of a straw, in case it comes to that. Because more and more he is having trouble with the mechanics, and the brain command to DO the mechanics, of eating and drinking. Sometimes, he forgets in mid meal after he was just doing decently. Often while drinking, once the glass is half empty (yes, yes I know Hap would say half-full) he holds it to his lips but can’t get any. I have to remind him, tip your head back, dad… and so far, that helps and he is able to get the rest out. As for the solids, well, it’s a mess. He probably can’t really use both hands with a knife and fork, so he uses one hand or the other and a fork or spoon to feed himself. Today, he began with his jello (that’s another thing I refuse to correct – I am gonna let that man eat dessert first!) and yes, it is messy. They usually put a giant sized bib on all the residents, which early on seemed so wrong for my dad and he often didn’t use it, but his skills have deteriorated so it IS useful – but I don’t think he is any more aware of what it is or that someone placed it on him than he knows what day today is. Since he had used his spoon with the jello, he dug in to the green beans with it next. That didn’t work as well, so I suggested the fork. But until I replaced the spoon with the fork in his hand myself, he did not make the change. And so, it is messy, but I don’t help him unless he physically will not feed himself. I figure, the longer he can do something, we should encourage him to do it, if for no other reason than to give him something to do in a long, long day of sameness. But again – that’s me talking. His day may seem full and exhausting to him, and in fact I don’t think his day is a day at all. I think he cycles in about three hour increments. There are days he is fabulous at lunch and terrible at dinner, and days that mom comes home saddened because he seemed so bad at lunch, but when I go for dinner he is a new man. Such is this disease – whatever it is.

Now that my dad is more ill, and he is safe and cared for, and my mom is doing decently and is healthy, I have the luxury of feeling like these are not the worst of times. That enables me to have the best hour of the day with my dad, too. While he may be concentrating on his green beans, I can be nostalgic and remember who he was. And while, of course, I didn’t love him enough or thank him enough when I should have, I can now sing to him, songs I know he used to like, like Donna Wells “Happiest Girl in the Whole USA” or “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” by Lynn Anderson, or old country classics or folk songs. He liked “Green Green Grass of Home” and “Honey,” and Kenny Rogers songs. I can rub his shoulders while I talk to him, and if I have time for a real treat, I massage his arms and legs with moisturizer. Listen, I’m no saint – I put gloves on first, for his protection as well as mine. We don’t need to exchange germs and bacteria any more than we are anyway, and okay I admit it…I still get grossed out by bodies. But that is okay… because I know, no matter what level of sanity someone is at, it just feels damn good to have someone massage your arms, leg muscles, neck. I know why I love manicures and pedicures, and it’s not just because of the pretty polish.

I recently saw Amy Grant on tv, discussing caring for her elderly parents. Her mother had recently died after having dementia, and her father has it now. She was distraught that this was what the final chapter was like for two faithful servants like her parents, but she said that she was very moved by what a friend told her: this is the last great lesson your parents will teach you. Amy decided that if this was what her parents were teaching her, she damned well better be all in and learn it. While the choice is not a conscious one of my dad’s, God works in mysterious ways and I know that I am learning about myself, my husband, my family, and every individual I come across during this experience. Part of the best hour of the day is being forced to sit there and really not think of or care about anything but reflecting on my dad, on the life he gave us, on the relationship that we had… of all that he gave up, joys he experienced, how he has suffered. How much I owe to him. How unique and wonderful he is. How blessed I am that this hurts so bad, that I have nothing but good memories and that’s why this is so devastating. What a gift to be 43 and just now to have lost my dad, and what a gift to be so torn up about it. Some people don’t talk to their parents. Some people live far away from them. Some people are always fighting. I am devastated to lose my dad this particular way, but I am so blessed and grateful that it IS this painful, simply because of what that says about all that came before. Sometimes I wonder if my dad’s prayers are being answered. If he prayed his whole life for my mom to be healthy and live a long life, for his children to be healthy and prosperous, and for God to give him the suffering instead. I would not doubt it.

I know that the angels who take care of my dad (well first of all, I do know that they are not all, and not always, angels) do not know him at all. They don’t know that he was much more fun, kinder, more generous and loving than the person they take care of in the bed next to his or the room across the hall. All I’ve got is our example to show these people how remarkable he was. Do I love that every single nursing home and hospital so far has brought us people who sought us out, saying things like “wow, you girls and your mom sure do love your dad!” Hell yes. I’m proud that people notice, and I am sure that is part of my sisters’ motivation too. Not as in we want people to see us visiting so we get ‘credit’ – no, not that at all. Rather, it is what he truly deserves, and he also deserves to have people see it and know it – THIS is what love looks like when you have been such a wonderful father. Learn from him, people. This is a man we will never leave, never forget, never cease to thank and love and blanket with affection to show the world how special and superior he was. Everyone thinks this of their loved one, or most, I am sure. But, sorry – we are here to show you different, more. Hap Harral was in a league of his own.